A History of Possibility

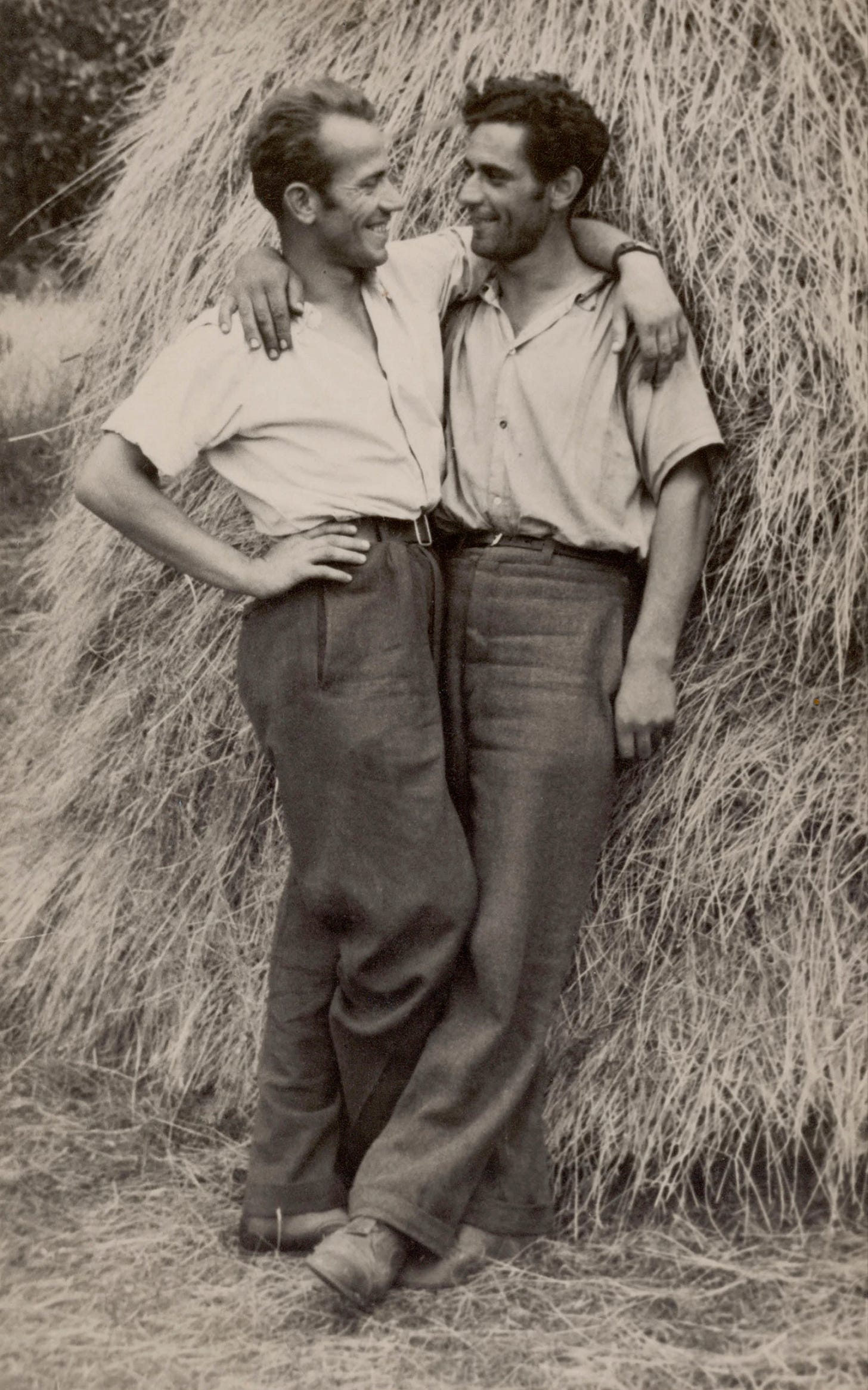

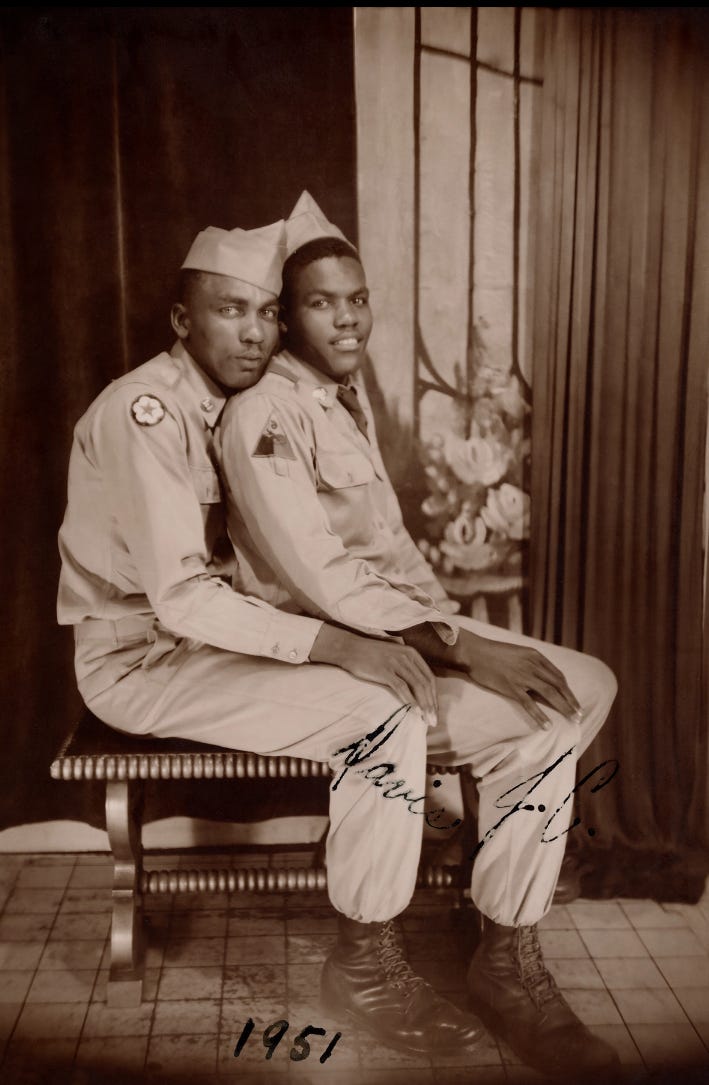

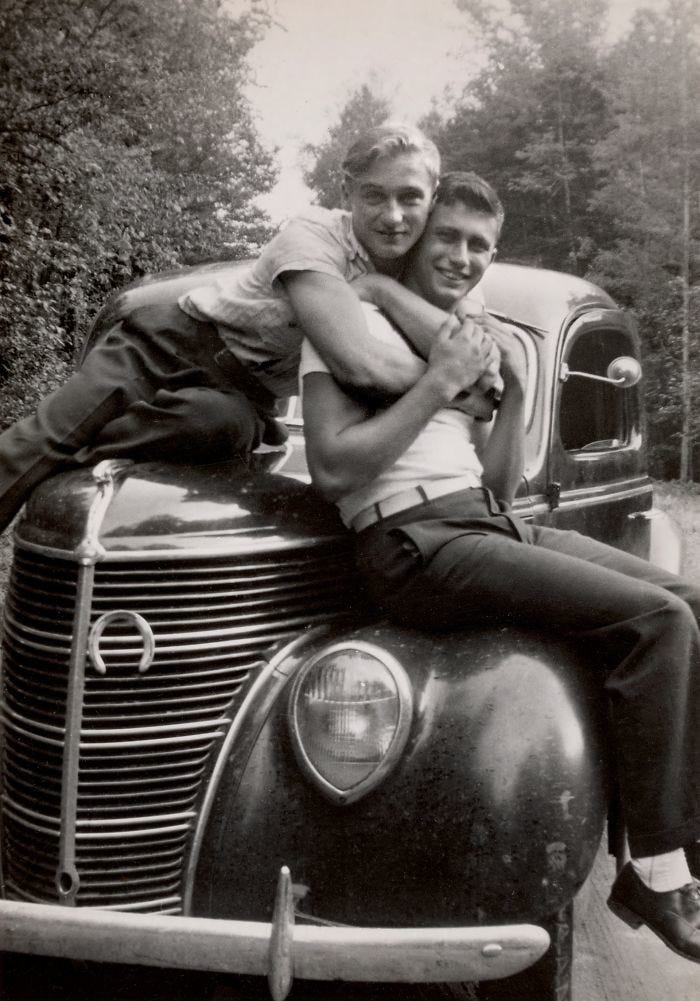

This week, I’ve been looking at photographs of men. Last year, I came to own the coffee table book Loving: A Photographic History of Men in Love 1850s to 1950s. A quick search through my inbox shows that I ordered it in December, which makes sense. It was a cold month. It was approaching the end of a very long year. I was living alone for the first time. I was not in love anymore. I wasn’t sure I had the capacity to be in love again.

The book contains photos collected by Hugh Nini and Neal Treadwell. In the foreword, they refer to theirs as an “accidental collection,” one that began twenty years ago when they came across an old photo they believed the be one of a kind:

“The subjects in this vintage photo were two young men, embracing and gazing at one another—clearly in love. […] Dating sometime around 1920, the young men were dressed unremarkably; the setting was suburban and out in the open. The open expression of the love that they shared also revealed a moment of determination. Taking such a photo, during a time when they would have been less understood than they would be today, was not without risk. We were intrigued that a photo like this could have survived into the twenty-first century. Who were they? And how did their snapshot end up at an antique shop in the Dallas, Texas, bundled together with a stash of otherwise ordinary vintage photos?

Then they found another. Then some more. Their collection grew to some 3,000 strong.

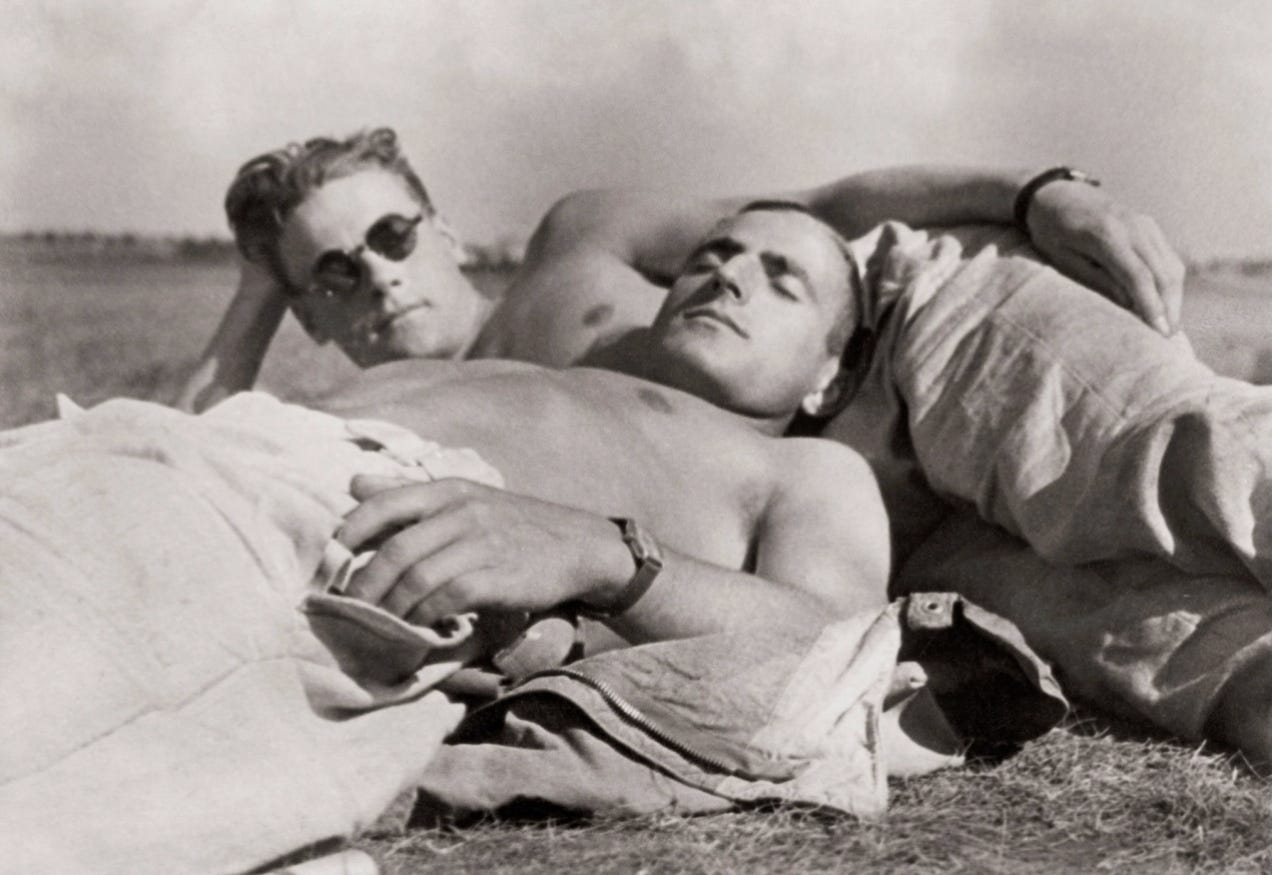

I’ve been trying to figure out what is it about these photographs that moved me so much. It’s partially the sheer fact of their existence—not just that they survived long enough to make their way into Nini and Treadwell’s collection, but that they came to be at all. There is no way for us to know the nature of these relationships. No way to know what brought these men to the moment of their photographs. No way to know what became of them and their love after the moment passed.

But we have these documents. We have these assertions of being, and of loving. It can be a mistake to interpret the past through the lens of the present, but I have to believe there was not an insignificant amount of risk to taking and developing and keeping these photographs. Their existence implies the existence of trusted friends or family members who took them, of understanding—or at least disinterested—people who developed them.

But there’s something else to it, too, and I think it must be this: the realization that these are my ancestors.

The concept of queer ancestry has always been a challenging one for me to grapple with. I’ll spare you (for now) the story of my rural, pre-internet childhood but suffice it to say that any sense of queer history I’ve developed has come about as a result of my deliberate searching. I didn’t grow up with queer elders in my family. When did I learn about Stonewall? Embarrassingly late.

When you aren’t taught your history, it can be easy to feel that you are without a history. When you grow up without a community, it can be easy to feel that your people don’t exist. When you don’t see examples of the kind of love you long for in the world, is it any surprise when that kind of love comes to feel impossible?

I think what these photos represent to me is a history of possibility. And if that possibility existed in the past, doesn’t it stand to reason it can also exist in the future?

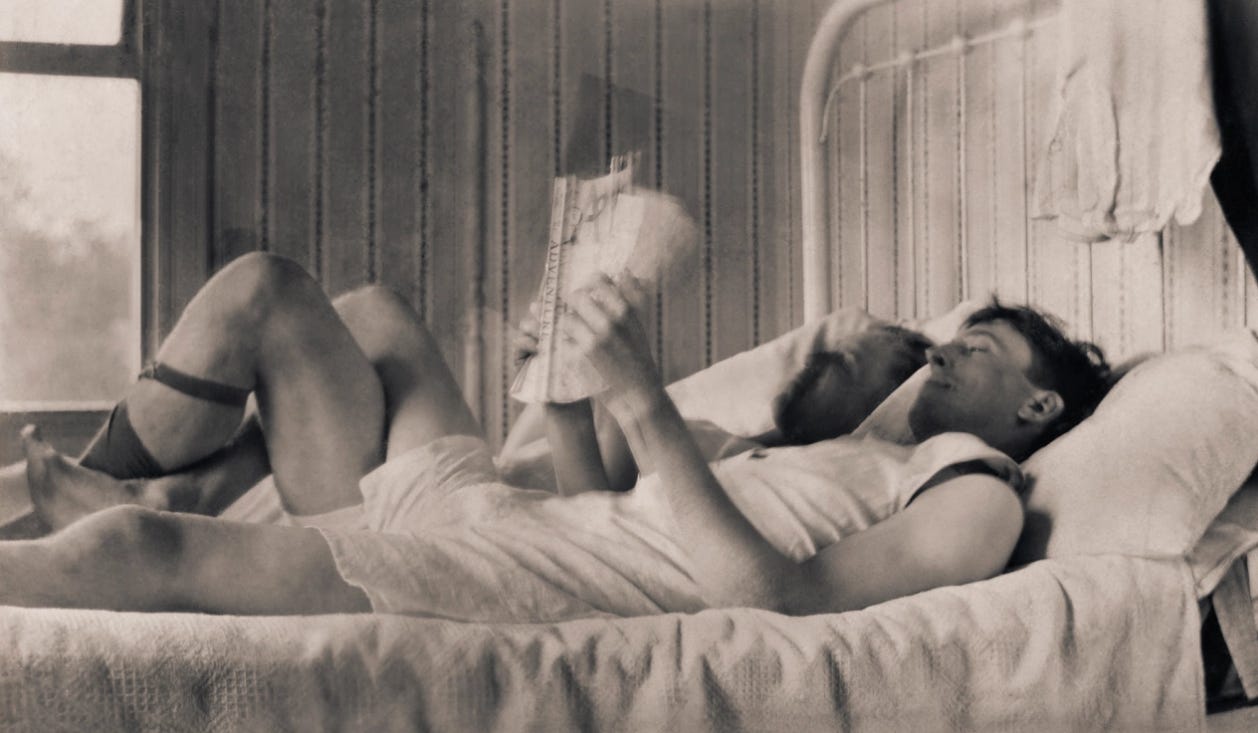

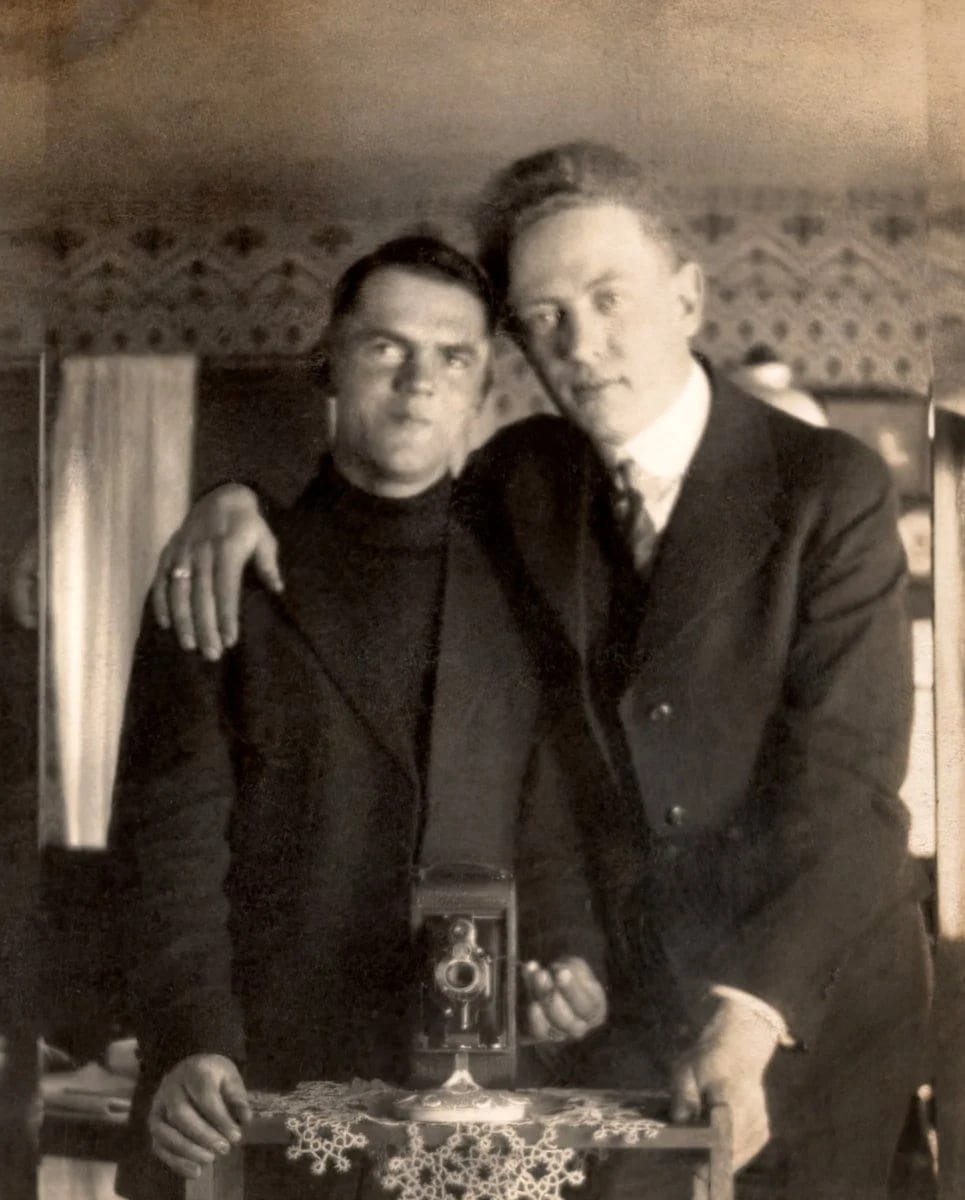

Okay, I also need to share with you my favorite photo from the book, a photo believed to be from around 1900. Nini and Treadwell refer to it as “the first selfie.”

How easy it is to ascribe to them a tragic backstory. Easy to assume they had no one in their lives they could trust to take a photo of them together, so they had to resort to their own means to document and preserve their togetherness. We are conditioned early to develop fluency in tragic queer narratives.

But we could just as easily—if, perhaps, not as naturally—ascribe a different story to the picture. An afternoon with perfect light. A deep and immediate desire to capture intense happiness, a happiness that could easily dissolve in the time it takes to leave the room and enlist a photographer. A mirror and a camera and an idea. A record.

What else?

For more retro gay photos and history to boot, I recommend Owen Keehnen’s Instagram.

This whole Twitter trend:

For the first time in history, Tony the Tiger is attending the #TonyAwards to surprise the nominees with golden bowls of cereal

Matt’s reaction to Bowen saying that The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom makes The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild look like “a proof of concept” in this week’s episode of Las Culturistas: